After watching nonstop Paul Giamatti commercials on Tubi I’ve realized two things: I don’t like Paul Giamatti and I hated the miniseries John Adams.

I read the popular biography by David McCullough on the first US Vice-President and influential Founding Father back in high school. It was fine. I don’t remember much about it to be honest, but that’s what prompted me to watch the miniseries.

The problem with the show is the same problem every dramatized account of a real historical event faces: there’s no surprises and every character is one dimensional. Unfortunately American history is largely mythologized. We all know it’s bullshit but we fall for it anyway.

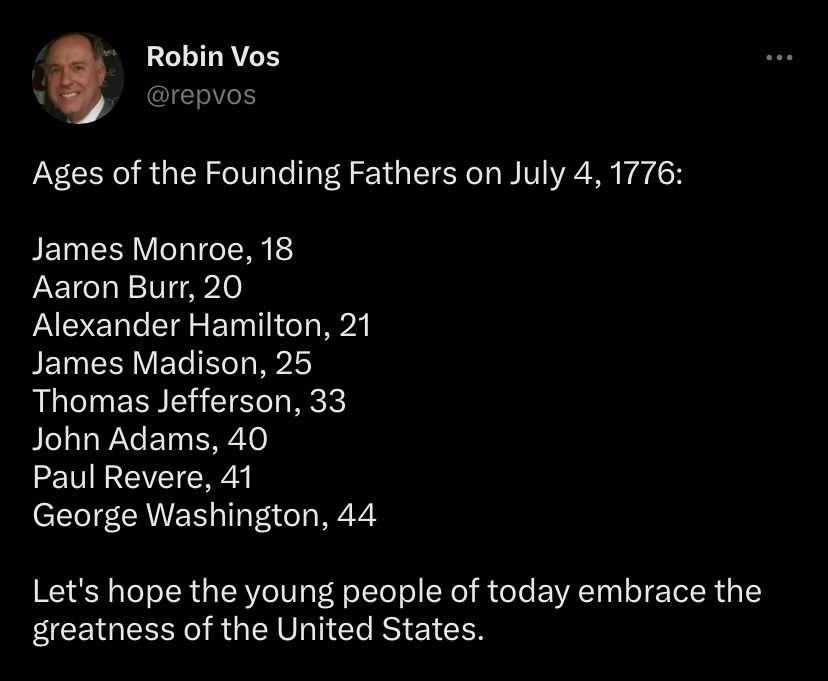

None of these guys knew what they were doing. But the Founding Fathers are always portrayed as paragons of virtue and certain in their destiny. I especially hated when John Adams meets George Washington. Why couldn’t Washington had been portrayed as an idiot who’s unfortunately the only man qualified to lead an army? That’s probably closer to the truth. But another thing that’s rarely discussed is how young these guys were:

While Washington and Adams were what we could consider “middle aged”, a lot of these guys were far from it. That’s an aspect that’s rarely explored and it would undermine the audience’s expectations; the “Founding Fathers” weren’t enlightened old men…they were young, dumb rich kids (and apparently the Revolution wasn’t all that popular with the working class, but that’s a story for a different day).

I also have a theory that if you travel back in time, understand the language and customs of the era, and observe a famous historical event as an invisible fly on the wall, you would have no idea what’s going on or what’s about to happen. This is especially true for ancient times.

I tried exploring this idea last year with the story According to Simon (which I never finished). Much like the Founding Fathers, this story also centered around a (probably) real historical event that has been heavily mythologized: the death of Jesus Christ and the founding of Christianity told through the “Apostle” Peter. To go back to the AD 30s Jerusalem and watch these events unfold, they would look nothing like they are portrayed in the Gospels or Book of Acts: Jesus is called Yeshua (in fact, Peter had no idea what the Greeks were talking about when they referred to him as “Jesus”) , the Apostles are a bunch of stupid young kids, Judas steals and returns Jesus’s body to Nazareth, and Paul is a lunatic who confuses Jesus’s missing body with a real resurrection. And in the midst of this madness, confusion, and political strife, a new religion is born.

Do I think events actually happened that way? No. But I do think my interpretation is far more historically accurate…and therefore more engaging…than the mythologies that have been handed down to us. Because every historical figure is a living, breathing, shitting, human being , storytellers should approach the subject from that perspective rather than regurgitate the same old myths that we all know to be untrue (and are largely stale).